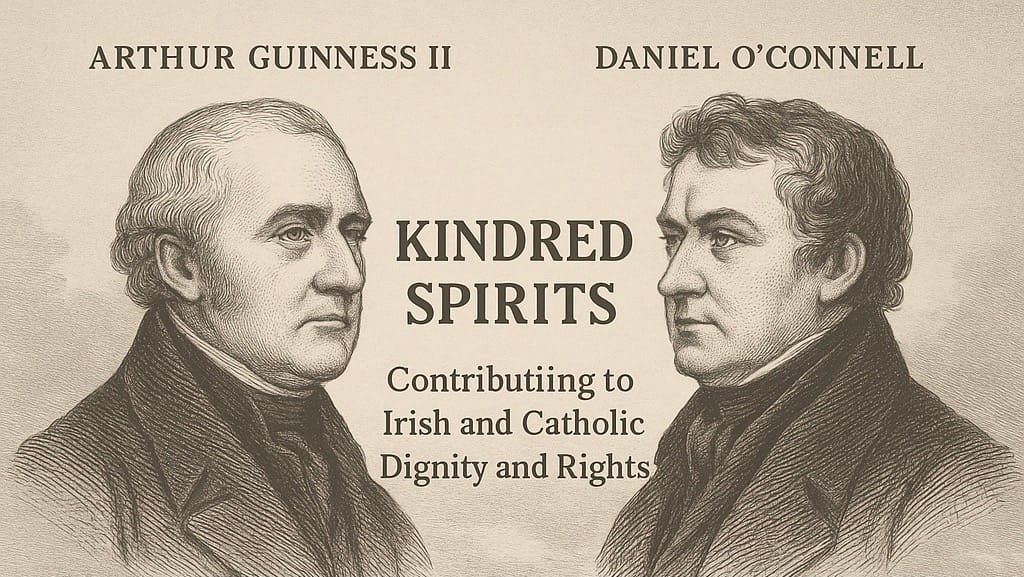

Kindred Spirits, Divided Paths

On Daniel O’Connell’s 250th birthday, a quiet Irish-history toast to Arthur Guinness II—his support for Catholic Emancipation, his hiring of Catholics at St. James’s Gate, and the political break that followed.

Two Irishmen helped shape modern Ireland — one from the podium, the other from the payroll.

This is a story about Daniel O’Connell and Guinness—how Catholic Emancipation, work, and politics briefly put the Liberator and Arthur Guinness II on the same side of Irish history.

Today, on the 250th birthday of Daniel O’Connell, “The Liberator,” I found myself thinking about a man you won’t find on the steps of Parliament: Arthur Guinness II. He wasn’t elected, revered, or hated in quite the same way. But for a time, the two men stood in quiet alignment — Catholic and Protestant, political firebrand and industrial reformer, both believing in the dignity of the Irish soul.

Their paths would eventually split. But their brief intersection — and the tension that followed — says more about Irish history than either story on its own.

“I Never Could Look My Catholic Neighbour in the Face…”

In The Guinness Legend by Michele Guinness, we find Arthur Guinness II, a Protestant landowner and businessman, celebrating the Catholic Relief Act of 1829 — the very legislation O’Connell had spent years fighting for. At a public meeting, Guinness stood and said:

“I am much joyed at the final adjustment of the ‘Catholic Question’… although always a sincere advocate for Catholic freedom, I never could look my Catholic neighbour confidently in the face. I felt that I was placed in an unjust, unnatural elevation above him…”

— The Guinness Legend, p. 38

It’s a raw and reflective moment. One Protestant man naming his own place in the system — and the quiet shame that came with it.

This wasn’t radicalism. It was conscience. And for a moment, Arthur Guinness II and Daniel O’Connell shared something rare in their time: moral clarity.

Guinness Hiring Catholics at St. James’s Gate

Guinness didn’t just offer sympathy. He offered jobs — Catholic jobs — at a time when doing so was controversial, even dangerous.

St. James’s Gate welcomed workers who were excluded elsewhere. It offered wages, stability, and welfare long before those were standard. That wasn’t just good business. It was a social stance — even if unspoken.

The brewery became a place where the divide between Protestant and Catholic blurred under the weight of shared work. For many, Guinness was a Protestant name you could trust — not because of its politics, but because of its people.

In a country defined by class and religion, Guinness hired across both.

The Break

But shared beliefs don’t always survive political pressure.

By the 1830s, O’Connell had turned toward repeal of the Union. His tone sharpened. His demands grew. Arthur Guinness II, ever moderate, pulled back. In 1835, he signed a petition opposing O’Connell’s candidacy. The backlash was swift and personal.

Supporters attacked the brewery. O’Connell’s newspaper The Pilot called it betrayal. And O’Connell himself — once friendly — now called Arthur:

“that miserable old apostate.”

— The Guinness Legend, p. 40

Guinness never apologized. He claimed he hadn’t moved — O’Connell had. But the rift never healed. One Protestant voice that had once quietly dignified the Catholic cause fell silent.

And as Michele Guinness writes:

“Never again would the Guinness family climb their way back into the Liberal fold, and one potentially moderating voice in the Catholic cause was stilled forever.”

— The Guinness Legend, p. 40

What Endured

Still — what Arthur Guinness poured into his brewery lasted. The jobs. The dignity. The subtle defiance of hiring Catholics when it would’ve been easier not to.

Even at the height of protest, Catholics returned to the brewery. Sales held. Attacks ceased. Because behind the politics was a workplace that had treated people right — and that is a power not easily undone.

It wasn’t perfect. It wasn’t heroic. But it was real. And that matters.

So today, we raise a glass to Daniel O’Connell at 250 — a man who gave voice to the voiceless.

And to Arthur Guinness II — the brewer who once stood beside him, quietly offering another kind of freedom: the kind you take home in your hands and in your wages.

Their paths divided. But for a time, they stood close enough to matter.

Comments ()