When the Price of a Pint Becomes News

In Ireland, the price of a pint isn’t just pub talk—it’s tracked, debated, and even used as an economic yardstick. Here’s what that reveals.

There’s quite a tizzy in Ireland right now—and it’s not about the new president or the upcoming Six Nations schedule. It’s about the price of a pint.

In Ireland, the price of a pint is not an abstraction. It’s measured. It’s tracked. And every so often, it becomes news.

In January 2026, Diageo announced a 7-cent increase at the wholesale level on a pint of Guinness. On its own, it sounds modest. But numbers like that never arrive alone. Once VAT is applied—and once publicans try to protect margins that are already razor-thin—the increase expected at the bar is closer to 20 cent per pint.

That’s the figure that caught attention. Not because anyone believes Guinness suddenly became more valuable, but because of what it says about the pressure pubs are under just to stay open.

The Irish Times illustrated the moment with a chart sourced from Ireland’s Central Statistics Office, tracking the national average price of a pint of stout from 2012 through late 2025.

The line starts just under four euro and climbs steadily—then more sharply after the pandemic. By November 2025, it crosses six euro.

The pint didn’t change. The conditions around it did.

Energy costs rose. Wages rose. Insurance rose. Everything required to keep a pub alive rose at once. The pint simply absorbed the weight.

Not Just a Feeling: The Guinness Index

This isn’t only pub talk or social media outrage. There’s a reason the pint keeps showing up in Ireland’s national conversation: people have been using it as a real-world yardstick for years.

Economists and commentators sometimes call it the “Guinness Index”—an informal, pint-sized cousin of the Big Mac Index. It’s often credited to Irish economist David McWilliams, who popularized the idea of using Guinness prices (at home and around the world) as a quick-and-dirty way to talk about purchasing power and whether money is “traveling” the way it should.

The History of Money: A Story of Humanity

by David McWilliams.

In one version, the math is almost disarmingly human: how many pints can an average weekly wage buy? Recent reporting has put that figure around 168 pints—better than the year before, but still well short of the 2007 peak. In another, analysts compare “pint-flation” to official inflation and note that stout prices have risen faster than the headline CPI in the post-pandemic years. The point isn’t to turn a pub into a spreadsheet. It’s to underline something Ireland already understands: the pint is a shorthand for affordability, and when it moves, people feel it.

Another version looks outward, comparing Guinness prices across cities and countries to spark the same old question behind every exchange rate: does money travel the way it should?

Call it economics, call it folklore. Either way, it proves the point: in Ireland, the pint isn’t just a drink. It’s a cultural touchstone—and, occasionally, an indicator.

What Ireland Tracks (That the U.S. Doesn’t)

What’s striking is not the increase itself, but the fact that Ireland tracks it at all. There is no equivalent national chart in the United States—no single line that captures the cost of a Guinness from coast to coast. Prices here are local, fragmented, and largely undocumented beyond menus and memory.

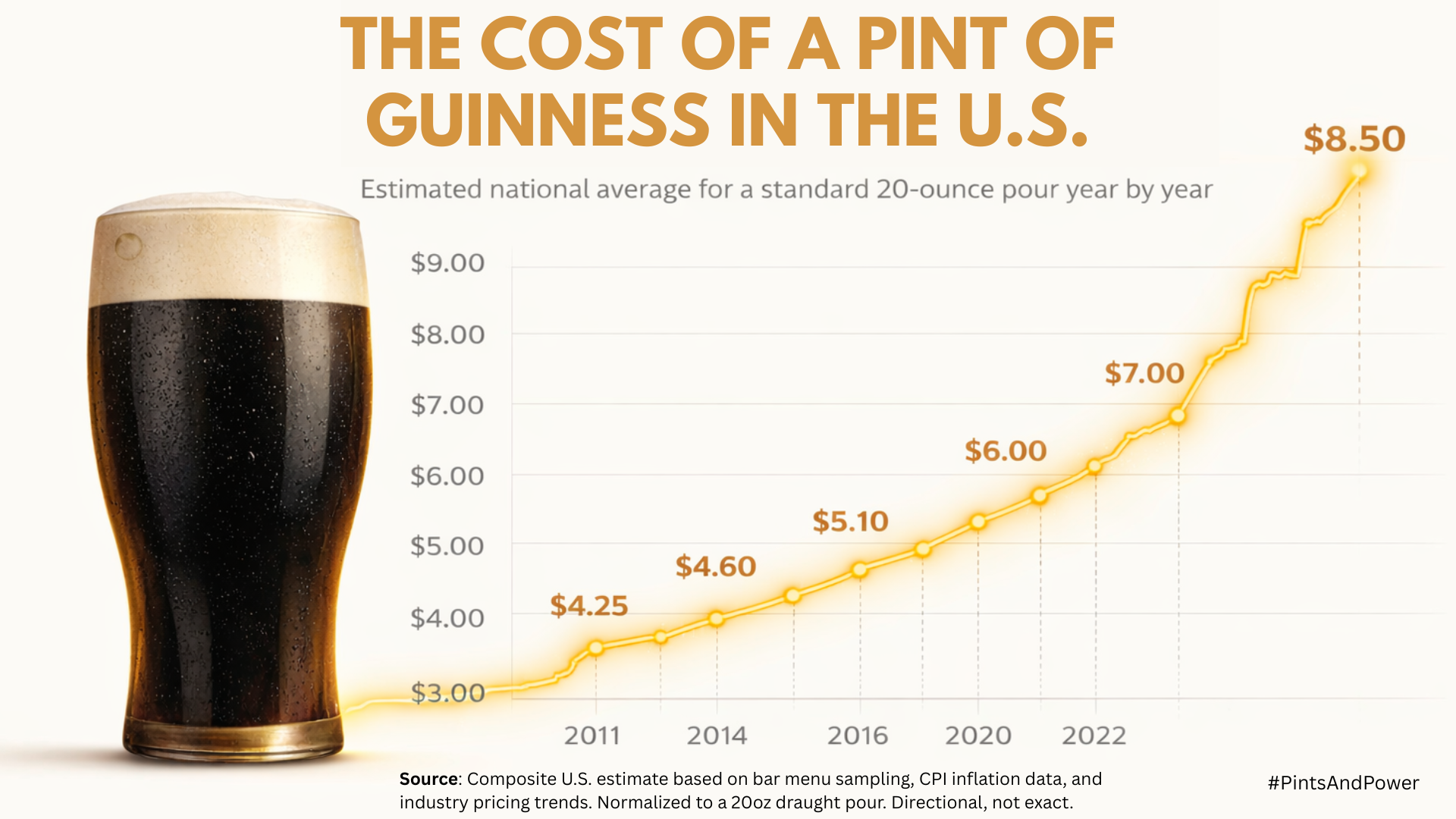

That difference became clear when I tried to answer the same question at home:

What does a pint of Guinness cost in the United States, year by year?

Out of curiosity, I turned to the web to try to find an answer.

To my surprise there was no simple answer. It took time. It hedged. It stitched together surveys, inflation indexes, proxies, and estimates. It explained methodology. It added caveats. Eventually, it produced something careful and qualified.

Source & Methodology

There is no single authoritative dataset tracking the national average price of a pint of Guinness in the United States year by year. Unlike Ireland, where the CSO tracks pub prices, U.S. pricing varies widely by state, city, venue type, and pour size.

The figures shown here are estimated national averages, derived from a composite of the following sources:

- Historical menu pricing and bar listings from major U.S. metro areas (Boston, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Dublin-style Irish pubs where Guinness is a core tap)

- Consumer price index (CPI-U) inflation adjustments for on-premise alcohol

- Industry reporting from hospitality trade publications and distributor pricing trends

- Spot-check sampling of published bar menus and crowd-sourced pricing databases over time

- Normalization to a 20-ounce draught pour to account for regional serving differences

These numbers should be read as directional, not exact. The intent is not to establish a precise price for every bar in every year, but to illustrate the long-term upward pressure on the cost of a pint in the U.S. and to provide context for recent pricing discussions in Ireland.

Local prices may vary significantly.

In Ireland, the price of a pint becomes a headline because the data exists. The CSO tracks it. The Irish Times charts it. When Diageo raises prices, the country knows exactly where that lands.

In the United States, even an artificial intelligence trained on oceans of data has to guess. Prices live on menus, in neighborhoods, in memory. A pint costs what a bar needs it to cost that night, in that city, under that roof.

The Quiet American Pint

For context, the pints I drink most often—proper 20-ounce pours at my local—cost $8.50.

Not in Manhattan. Not in an airport. In a local Irish pub that pours Guinness the way it’s meant to be poured: in a glass that settles properly, in a room that knows your name if you give it enough time.

Converted, that $8.50 pint lands at roughly €7.75 to €7.90, depending on the day’s exchange rate. In other words, it already sits above the current Irish national average—and squarely in the range Irish drinkers are now debating as the next threshold.

The difference isn’t the number. It’s the visibility.

In Ireland, a pint nearing eight euro is news. It prompts charts, statements, and concern about whether pubs can survive what comes next. In the U.S., the same price exists quietly, absorbed into the background of running a good pub—until one day the place is gone and the lights are off.

Why This Matters (Even If You Don’t Care About Prices)

So why should anyone care about this little brain exercise at all?

Because it exposes what we choose to notice, and what we don’t.

Ireland measures the pint because it measures the pub. It understands the public house as infrastructure: a shared room, a memory holder, a place where community lives. Tracking the price of a pint is really a way of tracking whether those places can continue to exist.

In the United States, the same pressures are real, but they’re invisible. Prices rise bar by bar, without a chart to mark the moment. You feel it only when a favorite place disappears—when the room that once held stories no longer does.

This isn’t about exchange rates or averages. The pint is just the lens. The question underneath it is whether we recognize the value of the places that pour it before they’re gone.

$8.50 isn’t cheap.

But it’s honest.

And when the price of a pint makes the news, it’s never really about Guinness. It’s about whether the places that pour it can still afford to keep the doors open—and whether we’re paying attention while they do.

Now, let that Settle In. This pint won't drink itself.

– Mike

Comments ()